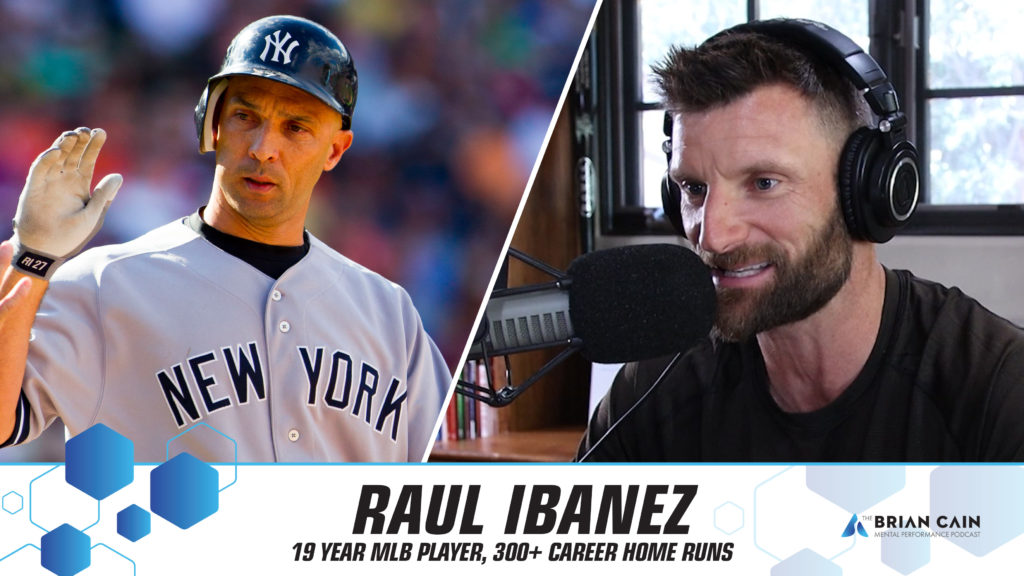

Former 19-year Big Leaguer Raúl Ibañez joins Brian to talk mental game and how it attributed mightily to his success. Raúl hit over 300 home runs and drove in more than 1,200 runs throughout his illustrious career…

You will learn:

- A fascinating story about how Raúl developed his obsession for baseball.

- How the mental game is “everything” in achieving success at a high level.

- A tremendous story about Mike Trout and what makes him so special.

- How Raúl defines success post-baseball.

PODCAST AUDIO BELOW

[powerpress feed=”peak_performance”]

PODCAST TRANSCRIPTION BELOW

“The mental side of things – it’s now in life I literally walk around thinking, “Well, I can do that; that’s not that hard.” I’ll have friends that say, “Dude, who you think you are?” – and I’m saying this humbly, Brian – and I’m like, “Wait, you don’t think like that?” I literally believe in my mind that you can will yourself to do anything.”

Raul Ibanez

Cain: Hey, how are you doing? Brian Cain, your Peak Performance coach, with another episode of the Peak Performance Podcast. Raúl Ibañez defines longevity, consistency, and excellence. He had a 19-year Major League Baseball career, having spent 11 of those seasons with the Seattle Mariners, while also wearing the jerseys of the Kansas City Royals, Philadelphia Phillies, Los Angeles Angels, and New York Yankees. A 2009 Major League All-Star, Ibañez had eight seasons with at least 20 home runs and two seasons with at least 30 home runs. He had six seasons with at least 90 RBIs and four seasons with at least 100 RBIs. In 2004 Ibañez tied an American League record with six hits in one game.

A 37th round draft pick in the 1992 draft, Ibañez had a storied career. He is currently serving as a special advisor to the Los Angeles Dodgers and frequently appears as a commentator for ESPN and ESPN Deportes. You’ll also hear his name pop up any time a managerial position opens up in the big leagues and someday, in my opinion, he’ll be a very successful Major League Manager. For more on Raúl please check out his Twitter game @RaulIbanezMLB. Please welcome to the Peak Performance Podcast, Raúl Ibañez.

Ibañez: Thanks, Cainer. Great intro. I really appreciate that. But you were off on one thing, brother – one thing. You said I was a 37th round pick, and I was a 36th round pick. I was one round better.

Cain: Unbelievable, man. That’s unbelievable. I love it. Wikipedia, I’m going to have to go in there and update that because that’s an absolute slap in the face to put you in there with the 37th round. How you weren’t a first round pick and made it in 19 years, that’s unbelievable to me.

Raúl, give our listeners a snapshot into your childhood growing up in Miami, going to Miami-Dade Community College, and signing as a 36th round pick and then having a 19-year career. Give us the journey into how you got to where you are.

Ibañez: Well, I acquired my love for baseball from my dad and my older brothers. We played tape ball. We didn’t have wiffle balls and all that stuff, so we played tape balls. Taped-up small baseballs and then just played outside in front of my house dinging that ball into our front door or the side wall repeatedly. The game was a line drive game. You could only get line drives. You couldn’t hit ground balls and you couldn’t hit popups because you were out. So that is where I started that whole journey.

Then I came up through the ranks like everybody else. Limited travel ball back then, a few months a year in the summer. Of course, in the spring you played all the time. Then I went to high school and that’s where I think I really started sharpening it. That’s when I knew I wanted to play baseball. I quit playing baseball for like, 18 months to two years. I think I just got burned out with it. Then I had a high school coach come up to me and say, “Hey, we heard that you were supposed to be a draft pick; what a shame that you don’t play anymore.” So I went back to this guy and said, “Hey, can I start practicing with you?” I started working with him every day and then, before you know it, that’s all I did. It was this insane obsession where you could find me any time hitting off of a street cone (like one of those construction cones) and 6-7 baseballs I had just hit over and over and over again and just visualized myself in the big leagues.

I went to Miami-Dade and played there for a year and got drafted. I got drafted out of high school in the 54th round and then I got drafted out of Miami-Dade. I was supposed to be a top 10 round pick. I had a really good season.

My dad passed away that year. Two months before I signed my dad passed away. I got called in the 16th round. Meredith called me in the 15th round and said, “We’ll take you in the next pick. Will you sign?” I said, “Absolutely!” They called me back in the 36th round and said, “We can’t give you that money.” Quite frankly, I just left because I got tired of hearing my mom cry every morning. After my dad passed away, that’s all I heard every day, so I literally took the $15,000 and the school and said, “I’m going to go make mine in pro baseball.”

Cain: Wow. One of the things you just mentioned was taking batting practice and hitting off of a damn construction cone as a tee and visualizing yourself playing in the big league. Raúl, how important was mental imagery and visualization in your game?

Ibañez: I swear to you, if you talk to my older brother – we had this job at Carnival Cruise Lines (and my dad worked at Carnival Cruise Lines). We had this job that we got through my dad, and it’s going to sound funny, but we made fruit baskets. You go on a trip, you put fruit, bananas, cheese. I still remember the order. It was like four oranges – it was like the most tedious, monotonous job. It paid well but it was tedious and monotonous.

I joking (half jokingly) say all the time that I got to the major leagues because of that job, because I’d sit there for 4-5 hours in a row and we’d go dead silent, my brother and I, and just do this monotonous, tedious job; and my only escape from it was visualizing myself in different major league ballparks, visualizing myself on different college fields, visualizing myself getting hits off with the best pitchers in the district in high school. I half jokingly say that’s where my mental imagery really helped assist me in this journey.

Cain: That’s unbelievable. Talk about maximizing your time. That’s like a story of a damn documentary. From making fruit baskets for Carnival Cruise Lines to a 19-year Major League Baseball career. I love it. Raúl, if you had to talk about the mental game, what is the mental game to you?

Ibañez: The mental game to me is everything. Now I’ve had time to back away from this whole thing that just happened. This thing that I was blessed with to play for that long. The mental game is everything to me because it starts with passion. Now I look back on it and I go, “What just happened? How were you able to do that?” You’ve got to have the passion. That is the driving force. That is the fuel. That is the wind through your sail – whatever you want to call it. That is the gift. The gift is the passion because that is what keeps you driving forward like a maniac.

To get to the highest level it requires – some guys are incredibly gifted and talented and there are not that many of those guys, believe it or not. Most guys, it’s just different variations of something that they do really well. But most guys have that passion and that drive at the highest level. It’s actually more common to see the passion and the drive than it is to not see it. Occasionally you do, but most of the time it is.

But the mental side of things – it’s now in life I literally walk around thinking, “Well, I can do that; that’s not that hard.” I’ll have friends that say, “Dude, who you think you are?” – and I’m saying this humbly, Brian – and I’m like, “Wait, you don’t think like that?” I literally believe in my mind that you can will yourself to do anything.

Brian, I saw you last a couple of years ago. You told me you were going to start getting in shape and you were going to start working out and you were doing like yoga. Maybe to you you were on that journey but I haven’t been with you on that journey every day, but to me that is astonishing. That is fascinating to me. A couple years ago I saw you and you were like, “Yeah, I’ve got to get in the gym more, I’ve got to get in the gym 3-4 days a week” and now you just did a triathlon. We can will ourselves to do anything and that is really what I believe about the mental game.

Cain: It’s unbelievable. Like, as you said, you just get to a place in your life where you get that mindset that I think you can do anything if you have the right training. You can do anything if you’re willing to commit yourself and put yourself on that path. Is that a mindset that you see common amongst all the guys you played with for 19 years of Major League Baseball, and is there any kind of mental game traits that you saw were consistent across the board besides just that passion and that drive? Is there a confidence? Is there a routine? What are the things that kind of popped up that you saw?

Ibañez: You see a lot of confidence but the confidence – you also see the insecurity. People think that insecurity is a bad thing. Insecurity can be a great thing because insecurity keeps me humble. Insecurity keeps me thinking that something is about to catch me. That keeps me driving forward. That keeps me focused on routine. That keeps these guys focused on their routines and forces you to do your due diligence and forces you to try a new exercise and allows you the open- mindedness to pick up a suggestion from somebody else and go “hey, that could make me better.” So having the balance of confidence and being humble enough or having a little bit of insecurity to go with that confidence keeps you sharp.

I think the drive, the competitiveness, the best players I was so fortunate to play with were incredibly competitive. I mean, I got to play with Mike Trout for about four months. You could literally get Mike Trout – if you challenge him, you can get him to do just about anything on the baseball field. You can go, “Hey, I can beat you at this” and you could – Mike Trout would stand at center field during batting practice. There was this little tiny hole in the center field wall. After he’d take his ground balls, his fly balls, and take his batting practice, he would be challenging himself to throw a baseball through this tiny little hole in center field. A tiny little hole that the ball barely fits through. He would just sit there over and over. You could hear the cheers from himself when he would do it every time he accomplished it.

I took batting practice with him for 6 weeks in spring training and there was a garbage can up on the hill on the left center field, and he’s trying to hit baseballs into the garbage can. The garbage can is like 420 feet away. I watched him do it well over a half dozen times in spring training. You can ask his teammates. We’ve seen him do it.

He is a guy that is constantly – he is not just the most talented guy but he is also fiercely competitive and constantly pushing himself. I think that’s a trait that you see amongst many major leaguers but especially the best ones. They’re uber competitive.

Cain: When it comes to competition, you mentioned like a measurement – Mike Trout trying to throw a ball through a hole in the wall or trying to hit a home run 420 feet away into a damn garbage can, which is unbelievable. In The 12 Pillars of Peak Performance, Pillar #4 is Measurement is Motivation. How do you use measurement as a motivator or kind of those numbers as a motivator for you?

Ibañez: Brian, that is why I love baseball so much – because you measure yourself every night. You have to. The way that you use measurement is you go – I don’t focus on the result. You don’t focus on – I focus on obviously the process. You focus on what you can control, what I did well, what I didn’t do well, reevaluate, and then come back.

The measurement part is key in everything you do. Everything. You’ve got to be willing and open-minded enough to receive feedback from people that you trust and use the measurement properly. The data is there for a reason. Ultimately, at the end of the day in a game like baseball, either you did or you did not. At the end of the day, that is what is accurate. Now they’ve gotten a lot better at figuring out what you did well actually means. They’ll measure exit velocity. They’ll measure hard hit contact and ratio, and ground balls to fly balls ratio, line drives, launch angles – they measure all of that stuff. But that burden is on the player to constantly challenge himself when no one is around.

Harvey Dorfman (who was one of my mentors that we talked about before) used to tell me all the time, “Who you are is what you do when nobody is watching.” That’s where you really make your strides forward is when nobody is around, when you’re in the cage by yourself, when you’re in the gym and nobody is watching. When you’re in the gym and people are watching and nobody knows whether you’re giving your all, but only you know deep down inside did I give my all today, and being brutally honest with yourself and being a hawk so vigilant with your own thoughts that you go calling yourself out and not making excuses for yourself. I think that is all a part of measurement too.

Cain: If you would, Raúl, talk a little bit about kind of your relationship with Harvey Dorfman. I know you played with the Phillies or Roy Halladay and Jamie Moyer had talked a ton about the impact that Dorfman had in their career. Jamie Moyer in his book Just Tell Me I Can’t – the whole book is about his relationship with Harvey Dorfman. Then you played with the Yankees and with Alex Rodriguez, who was a Dorfman guy. Talk a little bit about Harvey and some of the things that he taught you in your relationship with him.

Ibañez: If I had not met Harvey, if Jamie Moyer did not introduce me to Harvey back in the year 2000 when I was a fifth outfielder, third string catcher on the Seattle Mariners, I wouldn’t be having this conversation with you – unless we ran into each other on the subway or something.

I had one foot out the door. Harvey Dorfman – I went and spent three days with him at his home (that’s how he used to do it) and he pretty much helped me and taught me how to remold myself, how to build myself back up mentally and how to be vigilant with my thoughts. Harvey was fantastic because he’d just call you out. He’d listen, he’d ask you questions, he’d totally Jedi mind trick you, and he’d just ask you the questions and get you to say what he wanted you to say and then he’d zap and blast you on the spot. He’d say stuff like, “Oh yeah, they were on you a little bit for not driving in runs. That’s perfectly normal, but you’re not effing normal – you’re a Major League Baseball player, you’re a Major League All-Star, you’re not normal. Deal with it.” So he’d build you up a little bit then he’d punch you right in the chest with it. It was so practical and so brilliant and so simple. It was all of these things. So without him I wouldn’t be here.

And you talk to the guys that had the privilege and the honor to work with the great Harvey Dorfman – like you said, guys like Roy Halladay and Jamie Moyer. We were on the same team and occasionally Jamie would say, “What would Harvey tell you?” We would say that to each other at times – “What would Harvey say?” or “You know what Harvey would say.” So just the impact that he had on all of us from that perspective is just extraordinary.

Cain: You were with a bunch of other organizations. Are there other mental game guys that you came across in your 19 years and were they as effective as Harvey? If so, how come and if not, where were some of the breakdowns that you saw?

Ibañez: I mean, there are guys that are really good. As far as organizational guys go, there is a guy named Jack Curtis. He did a fantastic job. He uses hypnosis and affirmations. He actually spent a lot of time with Harvey. He’d fly down on his own dime to go spend time and learn from Harvey. He did a great job.

I think the breakdown within the game of baseball – there is obviously Brian Cain, who is a beast stud, but we’re talking about within the game. I think sometimes within the game – it’s breaking down now some, but people used to look at the sports psychologists like if you’re talking to him there must be something wrong with you. I think I’d love to be able to get to the point where they go, “You’re talking to him – there must be something right with you.”

The Yankees use it very well. Joe Girardi encourages it. It’s backed by Brian Cashman. They use Chad Bohling as part of meetings, and Chad uses video and they’ve integrated very well. Most other Major League teams, they just have it; it’s there for you, but you have to kind of go out on your own and do it and seek it, but it’s there. It’s there. Every Major League team has someone that does it.

The reason I think Harvey wasn’t only great at what he did and just incredible at what he did, but I think it was also that time you spent alone with him away from the stadium. He was working for Boras Corporation back then. Having that time by yourself to just go out there and pour your heart out and say “Here’s what I’m struggling with” – that’s why that situation was so unique and special. He was just incredible.

Cain: That’s awesome. I think one of the things that Harvey probably talked with you about at some point was how do you define success for yourself as a player and, Raúl, how did you define success for yourself as a player during your career? Was it simply a home runs and RBIs thing or was there more to it than that?

Ibañez: I mean, at the end of the day you had your long-term goals but the daily goals I’d define success – I was in the consistency of my approach and my routine. If I can come in and do the mundane and the everyday normal stuff, if I could do that with the same zest and passion every day, I knew I’d have a much greater opportunity to be successful. So I would look at the end of the day – I would sit there at my locker and even during an 0-4 I’d be pissed at myself, but I’d go back and I’d look and I’d go, “Hey, I did everything in my power today” or “Did you do everything in your power today?” And then I’d say “What happened?” and then I’d go “Okay, what am I going to do next time?” That was my evaluation afterwards.

But I’d define success as barreling up the baseball. I even took it one step further. If it was a barreled-up baseball on a good sling that I popped straight up and it was on the barrel, I’d define that as a semi-successful at-bat. There wasn’t a stat for it but I’d go, “Okay, I’m right where I need to be, I’m close.” There is a lot of failure in baseball obviously and you have to play the mind game with yourself that “Okay, I’m one great swing away.”

There was one time in New York I was 0-4 on the day and I walked to Freddy Garcia (he was in the dugout) and I said, “Man, after that ground ball double play, what a big moment in the game; I feel like running down the first baseline, continuing down the right field line, jump the wall, and go home” because that is how embarrassed I was. I came up the next at-bat and hit a game-time homer in the 11th inning or something like that. Freddie comes up to me and goes, “How about now?” Like he is pushing me. “How about now you feel like going home?” That’s the point in baseball. That’s why baseball is the greatest game. You can go 0-5. You can be 0-12 and come up with a game-winning hit and nobody cares about the other 11 at-bats. You’re always one pitch, one swing, one play away from greatness.

Cain: I love that. That’s hilarious. I want to run and jump over the wall. I felt like wanting to run and jump into the lake at one point while I was doing this IRONMAN.

Let’s shift gears here a little from kind of performance on the field and talk about performance in the clubhouse. In a poll by Sports Illustrated they polled 290 Major League Baseball players and you were actually the second nicest guy in Major League Baseball behind Jim Thome. Why is it important for you to be a great teammate and what does it mean to be a great teammate?

Ibañez: To be a great teammate, even the nicest guy thing – and I’m so thankful that guys actually thought that way about me – I actually think it’s harder to not be a good teammate. All that means is it’s not just about being a good teammate; it’s about being a good person. It’s about being good to the people that park your cars.

When you come through the stadium security and the ushers and the gentleman that holds the door for you and the clubhouse assistants and being good to those guys, just saying “Hello, how are you? How’s your family doing?” and remembering a little something about them, that goes so long. We have an opportunity as Major League Baseball players to make a positive impact on the lives of others. It’s not that hard to get out of your own body for one moment and just go, “Hey, how are you? Hey, how did your daughter’s graduation go?” It’s just not that hard to me. I think there are a lot of guys (by the way) that do this. There are a lot of guys. And I just think a lot more should. I think it should be part of your contract, is to not – there should be a “not be a jackass” clause in your contract.

Cain: That’s awesome.

Ibañez: It’s not that hard to just be kind to people. You go to a restaurant and leave a nice tip for the waiter or waitress that worked hard for you. Be kind to fans. Even if you can’t sign, just say, “Hey, I can’t right now.” There are times on the field where you can’t sign an autograph because you’ve got work to do and you’re in between and you’re hyper-focused. Just acknowledge a fan and wave to them and say, “Hey, I really can’t right now.” That means something.

I think it’s just being conscientious of your surroundings and aware that your teammates have families, they have lives, they’re struggling too. You may be doing good but they’re not, so try to be a good teammate and not beat your chest. Uplift and encourage and say, “Hey, you’re going to be alright” and try and be a helpful teammate. I think that’s part of your job. Or at least it should be. Obviously not everybody does it but I think it should be part of your job.

Cain: Part of your job in 2014 – you signed and then getting released by the Angels and then a week or 10 days later you get picked up by the Kansas City Royals. During the season that year in 2014 they’re struggling; they’re about 48-50 of 100 games into the year on July 21. Your manager Ned Yost says that the team needed to improve its play. You led a players-only meeting. Players later in the year – Eric Hosmer and Lorenzo Cain – they credited the turnaround of the attitudes of the players to that meeting. The Royals then won 24 of their next 30 games. They secured the wild card. They go to the World Series in 2014 and unfortunately lose to the San Francisco Giants. But they looked at that meeting that you called in your last season as something that really turned that season around, and then I believe they won the World Series the next year. What was it that spurred you to cause that meeting and what did you guys talk about in there?

Ibañez: Well, I think that what spurred that meeting was watching, being a part. I got released and the Royals were one of the teams that called. Not the only team. But once they called I was really encouraged by the fact that you could be a part of something that hadn’t been done in 29 years. They hadn’t won the World Series since 1985. So I was encouraged by that. I was encouraged by the roster and how good they were when you sat in the other dugout.

Once I got there I realized, gosh, these guys are young, they’re vibrant, they can really play. Great kids. Great teammates. Really aware. Superstar people. But they didn’t know how good they were because they had been for years – if you get around veteran guys that maybe don’t do exactly what they’re supposed to do or teach or even if you get young guys that don’t listen, if you don’t get the right people in place that don’t show them how to win and what it means to be a winning culture and that moving the runner over from second base is a victory and everyone should come up and shake that dude’s hand and that means something. Playing as a team, that is something.

What the meeting was, was I think we lost like six in a row. We lost the first four in Boston after the All-Star break. What the meeting was, was essentially, “Look, I don’t know if I’m going to be here for two more days or two weeks or two months or for the rest of the season, but it would be a crime if I don’t tell you how good you are. It would be a crime if you guys didn’t know that it matters to move runners over, it matters to play as a team, and that at the end of the day nobody cares how many hits you got. They don’t care about the W in the win column. That’s it.” So shifting that mindset and having them picture themselves as the best team in baseball.

One of the things that we walked out is, I said, “Look, I don’t care what has happened up until this point; our goal right now is to be the best team and the best record in Major League Baseball from here until the season is over – that’s our goal, that’s what this team is.” Lo and behold, they did it.

Listen, Brian, it’s like they say – you can’t make chicken salad out of chicken crap. It was all there already. They were already a great team. I think that they didn’t have a single-minded focus and purpose and they didn’t know how great they were. They have guys in there to carry that torch forward – guys like Hosmer and Moustakas and Tyson and Cain and Salvy and Esky – and they have this great culture. They fell short last year. They won, obviously, in 2015. They fell short last year but that team will be back.

This meeting was really a culmination of all the stuff that I had learned from Harvey, that I had learned from Brian Cain, that I had learned from Dr. John Eliot, that I had learned from Dr. Jack Curtis. These were all behind-the-scenes work trying to put the vision and the picture in their minds and making it vivid and having them even during the meeting talk about what champagne would feel like.

I go, “Guys, we have an opportunity to do something legendary here; we have an opportunity to do something that hasn’t been done in 29 years. That’s stuff where people will know where they were the moment you guys win the World Series, or the generations of Kansas City Royals fans that come behind you will be able to be associated and identify their Major League Baseball experience with a winning team. This is stuff that is culture – it’s bigger than us. This is stuff where the entire society, the community in Kansas City, will be able to identify you guys as winners for the rest of your lives; this is serious stuff. So 40-50 years from now you’re walking down the street and people will go ‘thank you.’” These are serious implications here and these guys just took to it and they did it, and they were just an incredible group of guys and I couldn’t be more proud to have been associated with them.

Cain: Well, it sounds like a lot of what you did is you helped create the vision, and it helped them get a little bit more focused maybe on the process and what it means to go out there on a daily basis and go out there with a daily purpose and a plan to win. I think a lot of times as professional athletes you guys are like dragon slayers and there is a mission every day where we’ve got to go out and slay the dragon, which is to win the game by winning the pitches. Then all of a sudden your career ends. You’ve been a dragon slayer for 19 years as a professional athlete and all of a sudden there are no more dragons to slay. What is the transition like going from playing Major League Baseball for 19 years into retirement where you’re no longer playing? What has that transition been like for you and how do you define success now for yourself in your life without baseball as a player?

Ibañez: Well, I’ve always defined success first and foremost as being a good father and the best husband that I can be. That to me has meant more as far as my own definition of success than anything I could ever do on the Major League Baseball field. That’s the most serious job that every man and every father has, is to be a good dad and to teach their kids and to love on them and instruct them and guide them. So that to me is first and foremost.

I think after being in that insulated bubble that is Major League Baseball where it’s a mentality of train. During the off-seasons my wife is building vacations and I’m building vacations around the quality of the gym in the resort, you know what I mean?

Cain: That’s awesome.

Ibañez: It’s this bubble and this obsessive compulsive disorder in a good way that you use positively. But then you step out of that world and first I look back and I go, “Man, that actually happened.” The kid from Miami that was the 36th round pick – not 37th, Brian, 36th.

Cain: Yeah.

Ibañez: The kid from Miami – this actually happened, my dreams came true. I go, “What was that? How do you do that?” So now it’s given me – I’ve failed so much that I’m not afraid to fail. I think that is one of the greatest gifts that Major League Baseball gave me, is I have zero fear of failure. I have zero fear of embarrassment or ridicule and I’m going to keep getting back up and I just keep driving forward.

I’m working at ESPN. I love doing that. I have a great time with that. Every once in a while I look around and I’m like, “Dude, I’m on SportsCenter right now.” I used to watch SportsCenter as a kid and I’m on SportsCenter with Chris Berman walking around and Bob Ley and these guys and I’m like, “I’m on SportsCenter with these dudes.” So it’s really cool and that’s just the most incredible thing, is to be a part of that and to be in that type of scenario and situation.

All of that came from the stuff that I did in Major League Baseball and my job with the Dodgers. I absolutely love being able to pour into the young guys all of these lessons. As you know, Brian, sometimes players will open up to another guy in a uniform more than they will to the performance coach. So just being able to give – your impact of the stuff that I learned from working with you is being felt. The ripple effect of that is being felt for hopefully decades to come because that’s how it works. Paying it forward. You give it to somebody else, they’re going to give it to somebody else and move it on down the line.

I really define success by helping others and the impact that I can have on others, on your family first and foremost, and on other people that could really benefit from it – the youth, players, my son’s high school teammates. So all of that is really how I define success.

Cain: Awesome, Raúl. Last question for you. I really appreciate you taking time out of your schedule to do this podcast. It’s been absolutely unbelievable. Last question for you. What is it that you know now looking back that you wish you knew when you were pre-draft or you were playing out of high school or playing in college – because a lot of people that are listening to this podcast are going to be high school or college baseball players – what do you know now that you wish you knew then?

Ibañez: This is a really tough one because part of that feeling of never thinking that you’re good enough and that nothing you did was good enough and that anything you did was enough, part of that feeling is maddening. It drives you nuts when you’re not there, when you’re not around, when you’re at home and at 3:00 AM it wakes you up and goes, “You’ve got to do more tomorrow.” I wish I knew how to really enjoy the journey of this whole thing.

I see a lot of kids today – my son’s 15 and there are kids on his freshman team that are committed to play at D1 schools. I see a lot of these kids and I try to tell the kids all the time, “Listen guys, don’t play because you want something out of it; play because you love it, play because you’re passionate about it, play for the pure love of playing.” Brian, I would have played Major League Baseball for free. I’m glad that they paid me but I would have done it for free.

I think my message would be somewhere in between try to balance the work and the drive and really enjoying it, having fun while you’re doing it. Not that I didn’t have fun. I did it because I loved it and I had fun. But at the same time that extra stress of, in today’s game where kids are trying to get committed to college and they’re trying to focus on “get drafted, get drafted get drafted” – enjoy the game. Love the game. Have a good time with it. Really enjoy the process of being in the batting cage. I love that process. I love the tiny nuances that I used to be able to figure out on my own. The last four inches before contact. I feel this. I love that, trying to pick apart and decipher that puzzle and enjoy that part of the game. Everything else will come.

Don’t play because you want something out of it. Play because you love it more than anything.

Cain: Raúl Ibañez, I cannot thank you enough. Unbelievable podcast. Thank you for sharing your experience, your wisdom. You’re going to make a tremendous impact on the coaches and players that are listening to this podcast. Absolutely unbelievable. Thank you so much.

Ibañez: Brian, thanks, buddy. Congratulations on the triathlon and thanks for making me better. Thanks for everything you’ve taught me. Our relationship continues to grow and I appreciate it. Thank you, bud.

Cain: Thank you, man. Make sure you all follow Raul @RaulIbanezMLB on Twitter. Thanks again for checking out the Peak Performance Podcast. Make sure you absolutely, positively Dominate the Day.